The first edition of the ILS show, presented by CCR Re in parallel with its quarterly ILS newsletter, provided the opportunity to review several topics associated with ILS and the development of the Paris Marketplace.

To discuss these topics, we brought together a panel of recognized specialists: Olivier Desmettre, Brigade Chief at the French Financial Supervisory Authority (ACPR), Benoit Liot, Chief Retrocession Officer at Scor, Edouard Chapellier and Patrice Doat, associates at Linklatlers, Stephan Ruoff, Business Leader at Schroder and Quentin Perrot, Senior Vice President at Willis Securities.

Here is a look back at the highlights of our discussions on Investment-Linked Securities that are becoming more and more known and understood by the investment world!

What is an ILS?

Quentin Perrot: An ILS—Insurance-Linked Security—is a financial instrument associated with an insurance risk. Basically, it is an investment that is made in the performance of a reinsurance contract, especially one used to cover a natural disaster risk such as an earthquake, a storm or a hurricane.

Quentin Perrot: An ILS—Insurance-Linked Security—is a financial instrument associated with an insurance risk. Basically, it is an investment that is made in the performance of a reinsurance contract, especially one used to cover a natural disaster risk such as an earthquake, a storm or a hurricane.

The use of ILS began about 25 years ago in the wake of two natural disasters in the US: the 1994 earthquake in Northridge and Hurricane Andrew in Florida which both generated tremendous losses. As the reinsurance market was unable to efficiently recapitalize following these losses, insurance companies sought to transfer their risks to the financial market in order to protect themselves against major losses from potential future events.

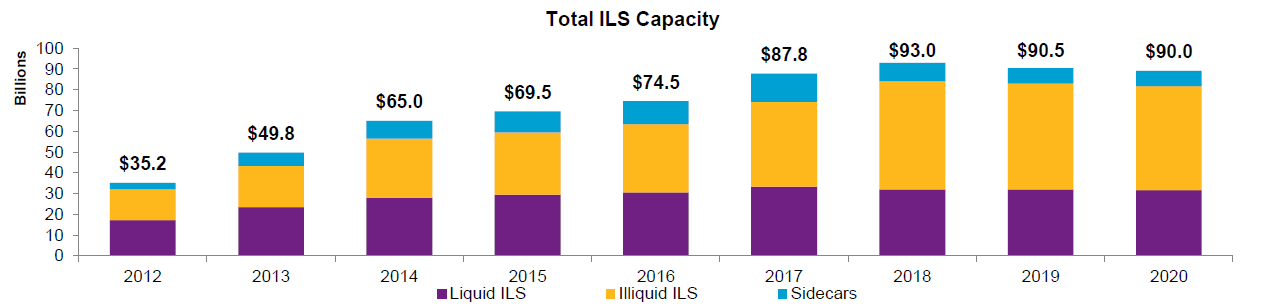

Today, after undergoing significant growth in the 2010s, the ILS market is valued at nearly 90 billion US dollars.

The two main forms of ILS investments are Cat Bonds and sidecars. In all cases, the principle remains the same: reinsurance risk is transformed into a financial investment. In this manner, it is the investor that assumes the risk instead of the insurance company in exchange for a risk premium.

Generally, a financial investor cannot legally underwrite reinsurance without a special license. This is where special French funds—called FCTs—and the Paris marketplace come into play. They enable us to use a vehicle that transforms the reinsurance risk into a financial investment.

ILS are used primarily to transfer natural catastrophe risks. Can other forms of risk be securitized?

Quentin Perrot: Yes, of course. A few years ago, Generali issued a cat bond covering third-party motor liability risks, to protect the company in the event of a sharp rise in these claims. They issued a few cat bonds covering terrorism risks as well. The International Federation of Association Football also issued a cat bond linked to the potential cancellation of the 2006 World Cup in Germany.

Quentin Perrot: Yes, of course. A few years ago, Generali issued a cat bond covering third-party motor liability risks, to protect the company in the event of a sharp rise in these claims. They issued a few cat bonds covering terrorism risks as well. The International Federation of Association Football also issued a cat bond linked to the potential cancellation of the 2006 World Cup in Germany.

Given that investors tend to prefer short-term risk investments, what about liability or financial risks that are more or less long-term? Can these types of risks be securitized?

Quentin Perrot: It depends on the duration of their development. If we are talking about nuclear disaster risk, for example, where it takes 20 years before we can assess the loss, it is true that you cannot very easily transfer this type of risk by way of a bond. Investors will prefer investments that are not correlated with the rest of the financial market. Natural catastrophes are the easiest type of risk to securitize and are typically more suitable in this type of situation.

Quentin Perrot: It depends on the duration of their development. If we are talking about nuclear disaster risk, for example, where it takes 20 years before we can assess the loss, it is true that you cannot very easily transfer this type of risk by way of a bond. Investors will prefer investments that are not correlated with the rest of the financial market. Natural catastrophes are the easiest type of risk to securitize and are typically more suitable in this type of situation.

How does a Securitization Mutual Fund (FCT) work?

Patrice Doat: The Securitization Mutual Fund (FCT) is a French-law investment vehicle that dates back quite a few years. It was first introduced in 1988. It is a statutory scheme that has proved its worth and is provided for in the Monetary and Financial Code, to some extent in the General Tax Code and, naturally, in the Insurance Code.

Patrice Doat: The Securitization Mutual Fund (FCT) is a French-law investment vehicle that dates back quite a few years. It was first introduced in 1988. It is a statutory scheme that has proved its worth and is provided for in the Monetary and Financial Code, to some extent in the General Tax Code and, naturally, in the Insurance Code.

At the outset, the FCT was only used to securitize bank debt. In this respect, it was immediately considered an exception to the banking monopoly, and today it is also considered an exception to the insurance monopoly. It may be used as an issuer-transformer. A number of reforms have been introduced over the years and the purpose of the FCT has become very broad in scope. FCTs can now grant loans, provide guaranties and sureties, receive or purchase risks—mainly credit risks with derivative products and insurance-related risks for FCTs that carry insurance risks.

FCTs are very often used to securitize a wide variety of different asset classes. These include financial debts for banking institutions (consumer loans, mortgage loans, automobile loans, etc.), rental or leasing debts and even commercial debts.

For FCTs that carry insurance risks, a specific scheme has been in place since 2008 but it was used for the first time to carry insurance risk by CCR Re in 2019.

How an FCT works is really quite simple. Several different actors are involved:

-

A management company—or portfolio management company authorized by the Financial Markets Authority—that initiates the creation of the FCT. It sets down the regulations that outline the fund’s characteristics as well as its modus operandi, describes its assets and liabilities, and then lists all the rules (rules for the allocation of cash flows within the FCT, accounting guidelines and regulatory rules) applicable to the fund. The company is the fund’s legal representative—it establishes all contracts—and it also performs all of the fund’s administrative, financial, and accounting management tasks. It acts as intermediary to the investors making all decisions involving the fund’s daily operations;

- A depositary (an authorized credit institution) that maintains the fund’s assets. The depositary also provides a posteriori control of the regularity of the management company’s decisions and monitor its cash flows;

- A screening officer, acting as a sort of security precaution, that verifies the legitimacy of the risks and ensures that the information communicated by the cedent complies with all requirements;

- The cedent, that transfers the insurance risks;

.png?width=1200&name=support-ils-show%20Linklaters%20(anglais).png)

On the asset side of the FCT, we have a transfer of risk to the cedent who signs the contract which can take the form of a retrocession agreement, a reinsurance contract, or even a derivative. On the liability side, the FCT will issue debt securities to the investors that, in most cases, take the form of shares or bonds but sometimes of liabilities governed by foreign laws such as Variable Funding Notes. Naturally, the securities are subscribed to by the investors.

An FCT carrying insurance risk operates in practically the same manner as that of any other FCT. It must however obtain prior authorization.

Four main rules must be complied with when structuring an FCT:

- The FCT’s maximum net losses must be limited to ensure that they do not surpass the total value of the assets;

- The risks that are transferred must be transferred definitively in the legal sense of the term;

- The FCT must be integrally financed at inception;

- The commitments made by the FCT, with respect to the cedent transferring the risk, must be given priority over the FCT’s commitments toward the investors.

What are the major advantages of FCTs compared to structures that are typically used in the Bermudas or in jurisdictions such as Ireland?

Patrice Doat: FCTs present a number of advantages for investors as well as for cedents.

Patrice Doat: FCTs present a number of advantages for investors as well as for cedents.

First, there is the fact that there is a statutory scheme that has been in place for a long time and that there are little to no contractual pitfalls. Hundreds of FCTs, perhaps even thousands, have been established since the outset and banking institutions use them daily. To this end, an FCT provides a level of convenience and legal security that is important for investors.

Then, there is a license from the French supervisory authority—the ACPR—that enables us to ensure that structuring and implementation was checked and complies with the legal framework.

The FCT, as a special-purpose vehicle, is not subject to bankruptcy. The legislative and regulatory guidelines for insolvency procedures do not apply which, once again, provides an extra margin of convenience and legal security to investors and cedents. This also simplifies things to a certain extent compared to other structures. The investors are guaranteed that the FCT will not become insolvent (in any case not because of bankruptcy) and

there is no need to grant sureties to the investors as the assets are already protected due to the very nature of the FCT.

Quentin Perrot: Most of the advantages that Patrice pointed out do not entirely eliminate all competition. For example, when we use an FCT in France, the cedent automatically has the right to regulatory recognition given that the ACPR has granted its approval. This is indeed very positive but it is also possible to build the same structure in Ireland. In this case, the CBI—the Irish regulator—would approach the French authorities so that the ACPR provides regulatory recognition under Solvency II for the reinsurance treaty. Not everyone will need to use an FCT today however.

Quentin Perrot: Most of the advantages that Patrice pointed out do not entirely eliminate all competition. For example, when we use an FCT in France, the cedent automatically has the right to regulatory recognition given that the ACPR has granted its approval. This is indeed very positive but it is also possible to build the same structure in Ireland. In this case, the CBI—the Irish regulator—would approach the French authorities so that the ACPR provides regulatory recognition under Solvency II for the reinsurance treaty. Not everyone will need to use an FCT today however.

What is more persuasive, particularly for sidecars, is that it is possible for an FCT to use compartments. As sidecars are renewed annually, the use of a compartment can facilitate successive renewal year after year. In Europe, no structure, other than Malta, has this type of flexibility.

FCTs possess another important advantage: the reputation of the selected marketplace. Some cedents, that are particularly sensitive about their corporate image, could prefer to turn toward France instead of other jurisdictions located on islands.

What are the main watch-points the ACPR considers when a company files for a license in the case of an ILS issued under French law?

.png?width=75&name=Olivier-Desmettre(1).png) Olivier Desmettre: When the supervisory authority is consulted by a foreign authority concerning an operation undertaken by a French cedent–i.e. a French insurance or reinsurance organization–it will first consider the operation’s motives and the impact that the operation could have on the results and the solvency of the cedent. We look at the effectiveness of the risk transfer and, obviously, we verify that the operation will not require arbitration between standards, between countries, or between banking and insurance standards.

Olivier Desmettre: When the supervisory authority is consulted by a foreign authority concerning an operation undertaken by a French cedent–i.e. a French insurance or reinsurance organization–it will first consider the operation’s motives and the impact that the operation could have on the results and the solvency of the cedent. We look at the effectiveness of the risk transfer and, obviously, we verify that the operation will not require arbitration between standards, between countries, or between banking and insurance standards.

When a securitization operation is performed in France, we strive to ensure that the requirements, which are European as they are set in the delegated regulations, are duly complied with. There are three requirements that reflect the three pillars of Solvency II:

- Quantitative requirements associated with solvency. We also closely examine the financing of the special-purpose vehicle as well as a number of elements associated with the assets in which the special-purpose vehicle will invest;

- Requirements linked to the system of governance in which the special-purpose vehicle will operate;

- The reporting and application requirements of the ACPR.

The fact that the license is granted by the ACPR, is this not an additional element of convenience for investors?

Stephan Ruoff: Yes, indeed. The fact that a reputable supervisory authority that provides its visa on the ILS issued in Paris is a very positive factor. Although, as Quentin explained, other jurisdictions are admitted under Solvency II, or are considered to be Solvency II equivalent, a domiciliation that is either segmented or regulated by a regulator with Solvency II will always be preferred by investors over a jurisdiction this is much less known, or that perhaps has a dubious reputation.

Stephan Ruoff: Yes, indeed. The fact that a reputable supervisory authority that provides its visa on the ILS issued in Paris is a very positive factor. Although, as Quentin explained, other jurisdictions are admitted under Solvency II, or are considered to be Solvency II equivalent, a domiciliation that is either segmented or regulated by a regulator with Solvency II will always be preferred by investors over a jurisdiction this is much less known, or that perhaps has a dubious reputation.

Is this important for Scor in the choice of a jurisdiction?

Benoit Liot: Yes. It is obvious that having a vehicle directly approved by the ACPR is an advantage for Scor, which is regulated and controlled by the ACPR. The fact that the supervisory authority for the vehicle is the same for the cedent simplifies the process, saves a significant amount of time and helps us to better understand the portfolio as well as the cedent’s motives.

Benoit Liot: Yes. It is obvious that having a vehicle directly approved by the ACPR is an advantage for Scor, which is regulated and controlled by the ACPR. The fact that the supervisory authority for the vehicle is the same for the cedent simplifies the process, saves a significant amount of time and helps us to better understand the portfolio as well as the cedent’s motives.

📺 Did you like this article? Don't miss the next one and receive the replay of the show 📥